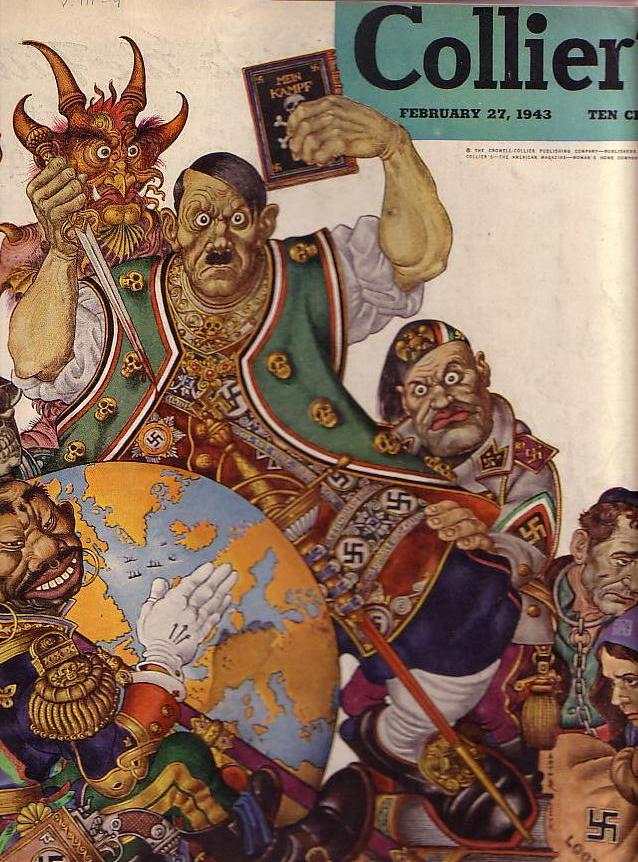

ONE FOOT ON THE GROUND is an article that appeared in the

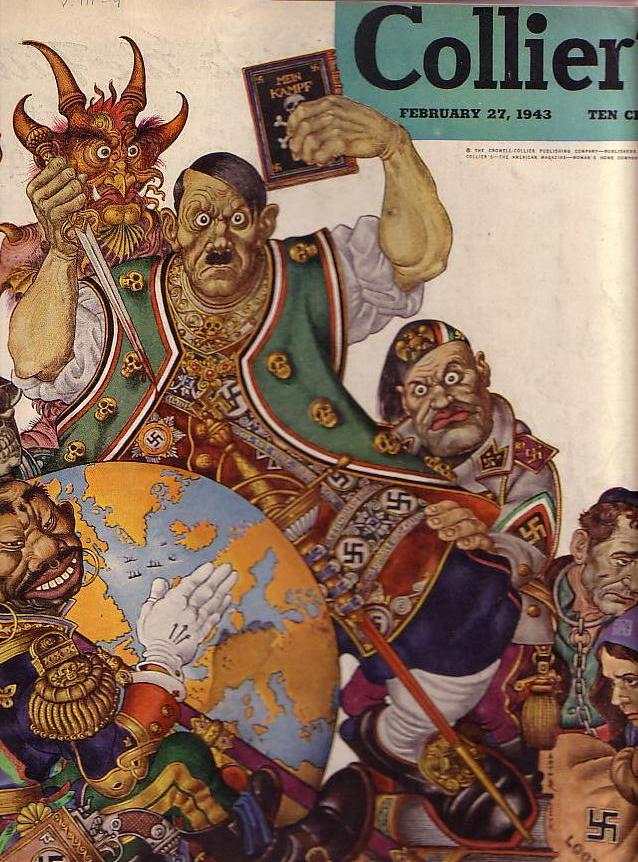

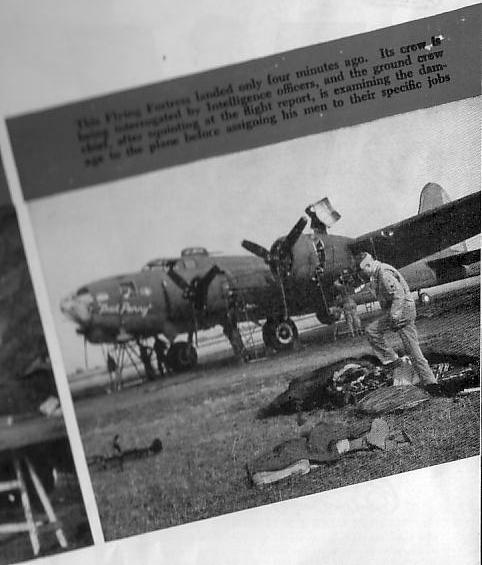

Now the big landing lights go on along the east west runway and the head-on silhouette of a four-motored bomber tilts down in the light and settles like a giant moth on the wet concrete. She taxies smoothly down the field, brakes to a halt, turns and rolls back to the line, warping into place as the landing lights go off again.

The landing lights come on again, another Fortress slides onto the strip and maneuvers toward her parking area, another group of mechanics run out to meet her. Still more ships circle overhead, awaiting their landing instructions from the tower. The shouts of ground crews are barely audible above the constant drone of motors: �Give us a hand with this dolly.� Toss me up that three-sixteenths socket, Joe� �Looks like a loose lead here��

His practiced hands twirl wrenches, reveal the tiny split at a bend of the feed pipe. Without looking up, he removes the faulty tube, replaces it with a new one an assistant hands to him, climbs down from the ladder, goes into the cockpit and starts Number three. He guns her, nods in satisfaction, cuts the motor. The ladder is shoved in close again, the cowling is fastened into position. Fourteen minutes, all told!

Another ship cuts her motors at the other end of the parking area; her flight reports shows that she pulls a little to the left when the brakes are applied. That may mean too little clearance of the left brake or too much on the right, the chief knows. Three thousandths of an inch difference is enough to cause a fatal ground loop when twenty tons land at better than seventy miles an hour. The wing jacks, huge worm screw lifters, are set under the jack points, two men turn the spindles, the fat wheels lift slowly off the concrete. The wrenches get busy, the broad brake bands are exposed. The landing gear expert makes measurements with his micrometer caliper; �Take up on the right one.� He turns the adjustment bolt carefully, stops to measure with his caliper again, turns the bolt some more. A final measurement; he moves back to let his assistant replace the cover, watching intently until the last lock wire is twisted to seal the nut securely. Just twenty one minutes!

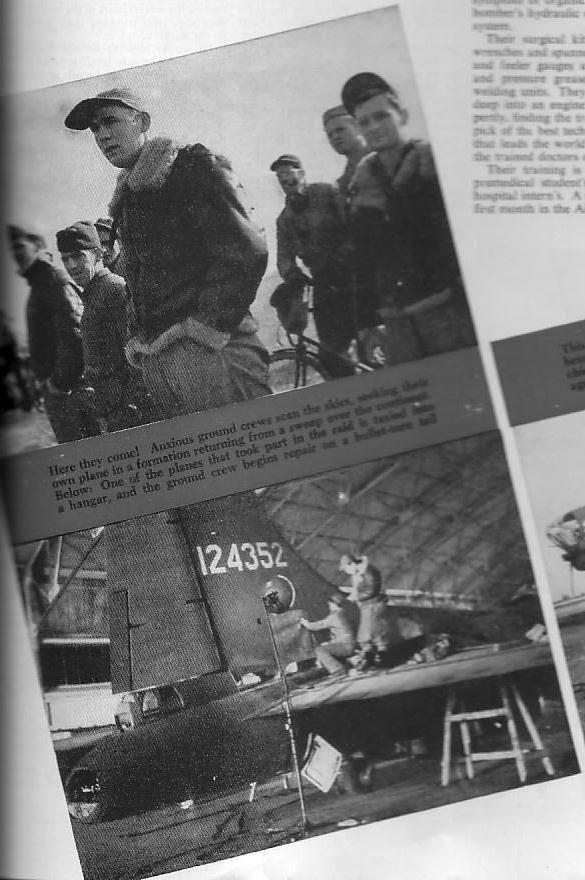

The lights flicking on and off in the darkness, the quick, deft movements and the ordered haste remind you of an emergency operating room in a field hospital. There is no waste motion here, no indecision. These men are specialists in mechanical medicine; They are skilled surgeons with X-ray eyes and stethoscope ears and hypersensitive finger tips. They tap and probe their patients with a family physician�s devoted care, diagnose each ailment, prescribe for the slightest symptom of organic disorder in the big bomber�s hydraulic, oiling or ignition system.

Their surgical kit consists of socket wrenches and spanners and micrometers and feeler gauges and air compressors and pressure grease guns and electric welding units. They plunge their hands deep into an engine�s vitals, feeling expertly, finding the trouble. They are the pick of the best technicians in a country that leads the world in technical skill. They are the trained doctors of the flying line. Their training is as exacting as any premedical student�s, as practical as a hospital intern�s. A mechanic spends his first month in the Air Forces learning to be a soldier, drill, manual of arms, taking and carrying out orders. In the classroom he brushes up on the rudiments of mathematics, takes machine shop and aptitude tests. If he makes the grade, he is sent to one of the Air Forces technical schools. Here he begins the long six days a week grind of higher math instructive movies, lectures, study of model airplanes, advanced theoretical and practical mechanics. He spends weeks tearing down, repairing and rebuilding motors, radials, liquid cooled, in lines, the tiny three cylinder sputter bugs of the single seater hedge hoppers. The thousand horse turbo supercharged power plants of the latest pursuits. He packs in all the theory and practice that engine doctors have stored up for the past forty years; and at last, at the end of the six months, he is assigned to work with a crew at an airfield, under the relentless eye of a grizzled Master Sergeant Crew Chief.

Master Sergeant �Chief�

Sergeant Billy Minor from

They�ve been gathered from the four corners of the

country. They come from the deluxe garages of

Give a thought, the next time you read about the big bombers carrying off a spectacular mission, to the anonymous heroes back on the line---the grease monkeys of the ground crews who sent them in there fit to fight.

They come from the heat soaked garages of the plains where the wind never stops blowing and the junk piles out back seem to sink deeper and deeper into the red dust. North, East, South and West, they thrill alike to the clean staccato of a combustion engine; they know that a motor is a beautiful and holy thing and they know their responsibility to that motor. If an oil line connection works loose, if a bearing pounds out, if a valve sticks, if ignition points burn and pit, if a gas line clogs, then a quarter million dollars� worth of fancy airplane will be grounded, maybe for keeps. They know it�s up to them at all costs, at all hours, in all weathers to keep �em flying.

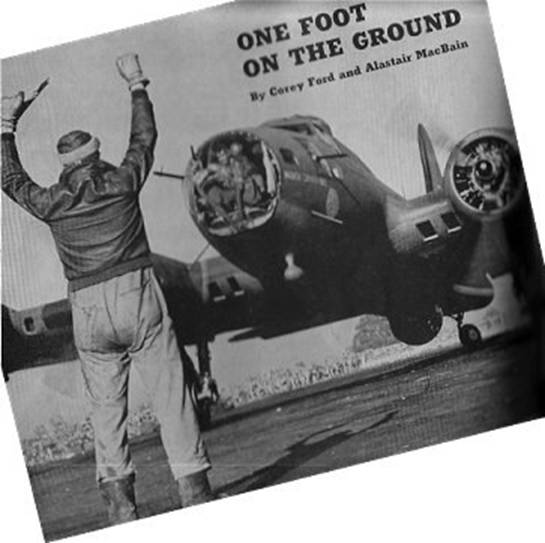

The lights on the runway have been turned off, all the other planes have landed, their ground crews are finishing up and heading in for late coffee and doughnuts at the PX before they hit the hay. Only one group is still waiting; they perch glumly along the workbench and on the metal chests in the tool shack, their cigarettes marking their locations in the dark room.

�It would have to be our lead and zinc mine that gets lost,� a voice complains. �The first date I made in town in a month, too.�

�Last anybody saw them was heading south to duck the storm.�

�Maybe one of her motors might have___�

�What are you getting at? Them motors were okay.� The cigarette behind the voice bobs excitedly.

�Keep your shirt on, Mike.�

�Anybody got the time? I said I�d phone by ten if I got held up.�

�Better tell her you meant ten in the morning. It�s half past now.�

�Suit me okay if we got assigned some other crate than that built in head wind.�

�You go ahead along on your date if you can�t wait. We�ll cover up for you.�

�And leave you guys to mess it up when she gets in? Hell, no!�

�Shut up! Listen!�

They pile out the door, stamping their cigarettes hastily. For a moment they hold their breath, looking up. They all hear it now, not clearly, but enough so there�s no doubt. �It�s her.� The sound comes closer, closer and passes directly overhead, a steady drone.

�Motors are okay,� Mike gloats.

Now through a rift in the clouds, they see her. �He�s signaling with his lights. Radio must be sour.�

She circles lower, her lights flashing a blinker code message. They look quickly at the tower. A green light appears in the window. She heads in, glides down quietly, barely ticking the cement, and skims to a stop. They race her to the parking place.

One of them holds his hands aloft, motioning her into

position: two others are ready with the wheel chocks; another ducks the blast

from her props and runs to open the door in the fuselage. The Crew chief

meantime moves under her big belly, turning his flashlight swiftly on her

wheels, her

�You run around with them young fellows,� he murmurs, �but you always come back to me.